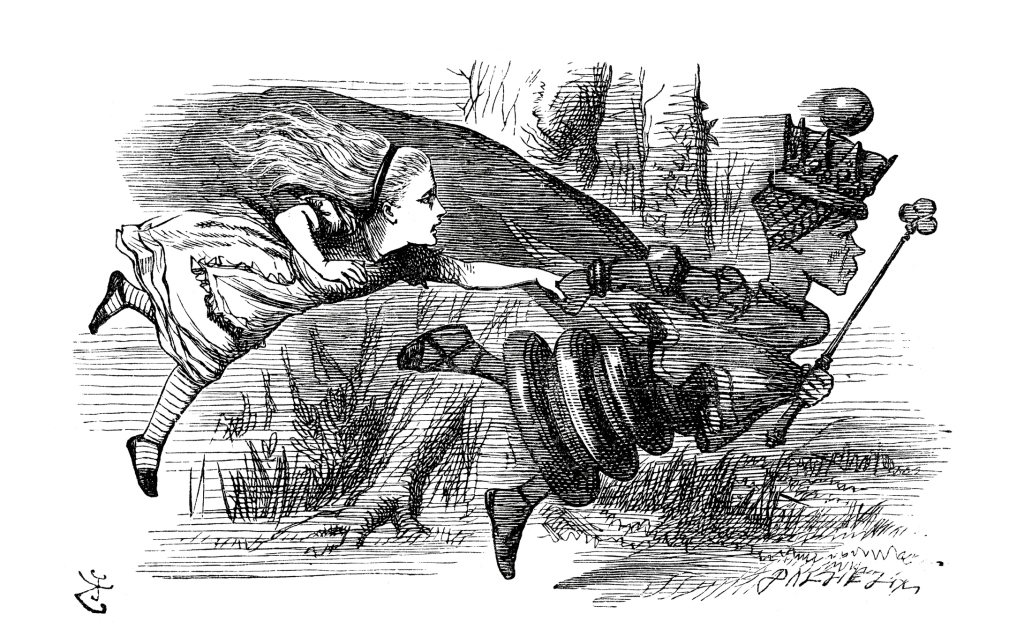

“Well, in our country,” said Alice, still panting a little, “you’d generally get to somewhere else—if you run very fast for a long time, as we’ve been doing.”

“A slow sort of country!” said the Queen. “Now, here, you see, it takes all the running you can do, to keep in the same place. If you want to get somewhere else, you must run at least twice as fast, as that!” —Through the Looking-Glass and What Alice Found There, Chapter 2, Lewis Carroll

There have been a number of high profile examples over the last several years concerning project management failure and success. For example, in the former case, the initial rollout of the Affordable Care Act marketplace web portal was one of these, and the causes for its faults took a while to understand, absent political bias. The reasons, as the linked article show, are prosaic and basic to the discipline of project management.

On the opposite of the spectrum was the fast-tracking of a Covid-19 vaccine. The full story on this success hasn’t yet been fully studied and documented, though there is sufficient raw material at hand. The politicization of the process and delivery of the vaccine has no doubt been a factor in the challenge in filtering out the noise from the peanut gallery. But it is clear that this vaccine and its subsequent boosters are one of the success stories of both project management and human resilience. Given an understanding of how that success was engineered will allow us to apply its elements that are not unique for other important undertakings.

There was a great deal of urgency in delivering the Covid-19 vaccine with the death and infection rates climbing on a daily basis during the initial surge of its introduction into the human population. This was the nightmare scenario that many virologists and health care professional feared, as if out of a Hollywood movie.

As in the world of the Red Queen, the health care community had to run very fast just to stay in the same place–to care for the ill, to deal with the existential threats, while simultaneously developing a vaccine that would allow societies to acquire immunity. Human civilization had to figure out how to reduce the transmission of the virus while still keeping the lights on. The issue of developing a vaccine required that that society had to “get to someplace else”—to “fast track” ?

Critical and Project Assumptions

Many times, when we read the headlines and reports critical of project achievement, the underlying assumption within the criticism is that we have a high level of confidence that we have the ability to control the variables and risk associated with the effort.

This is sometimes a result of improper analogies. Research and development are not the same as production. Opening up an additional assembly line will get more cars out the factory door. Opening up another lab may or may not result in expedited development.

But even acknowledging the difference between R&D and production, the criticism also presumes to accept the proposition that the assumptions used to frame the project’s goals were realistic. This is a fallacy.

According to a 2013 study by Arena, Blickstein, and others at RAND Corporation, it is these “framing assumptions” that are key in assessing realism over the project’s life. A later study by Arena and Mayer, also at RAND Corporation, built on this earlier paper by proposing a way of formulating framing assumptions in project management. When framing assumptions must be revised, it is an indication that the antecedent basis for undertaking the effort is at risk. At that point the effort essentially becomes a different project.

Project Resources and Risks

Among the essential assumptions in undertaking any enterprise—but particularly as it relates to project management—is that there is a goal (or set of goals) and a plan. The effort is cohesive and identifiable. As with any system, we understand that one must contribute the raw materials and energy necessary to produce the technology, the entity, or the end item that is the purpose of the effort. In our world this consists of resources including people—with their concomitant expertise—money, facilities, access to tools and equipment, and the means to leverage the achievement of each necessary event in the development of the item toward the ultimate goal.

This last element, which can be measured by technical achievement but also consists of information and learning, is often ignored. It establishes our system as having closed-loop feedback systems that allow it to evolve within the environment in which it finds itself. Without measuring technical achievement, effectively sharing information, and learning, we may deliver a website that cannot handle the expected volume, a vaccine that is not applicable to the conditions under which the virus must be treated, or an airplane that cannot land on an aircraft carrier.

In the case of Covid-19, the framing assumption here is that we possessed the means to “fast track” the development of the vaccine. The first order of business is to identify what exactly “fast track” means in terms of delivery. Does it mean by next year? Five years from now? As quickly as possible without a goal?

Let us assume that it is a goal that accelerates an established project plan. The project plan identifies a series of events that must occur through time in order to achieve the desired end goal of the project. The traditional approach is to throw additional resources at the effort. But this is not always the most effective route—and often results in a great deal of waste.

Depending on the risk in not achieving the end goal, the costs and waste associated with this approach may be viewed as inconsequential. We find this in historical examples where the threat that the effort was designed to address was an existential one. One obvious analogous example here is the Manhattan Project during the Second World War, where it was determined that the consequence of allowing Nazi Germany to first achieve the capability of producing an atom bomb would be disastrous to civilization. But then, in such cases, such criticism is irrelevant to the framing assumption.

But even in these special cases, where we are willing to accept a large measure of waste and alternatives that lead to dead ends, is the realization that any end item that requires specialized technical expertise will not always (and, in fact, very rarely) respond to brute force.

In the case of Covid-19 under Operation Warp Speed, the underlying technology using mRNA, as well as other technical lessons learned over decades at the National Institutes of Health (NIH) laid the foundation for success–an analogue that may be an outlier in effect, but useful in providing valuable insights. The procedures and protocols in handling these results amount to risk handling, which may include risk mitigation or simply risk acceptance. Earlier vaccine development efforts have not been so lucky or timely, but what has distinguished the NIH Warp Speed success has been the foundation of strategic planning for a rapid response protocol. This was learned from earlier failures to address such diseases such as Ebola. Eventually even these early failures turned into success in 2019.

In the risk-based world we are always running to try to stay in the same place. For when we use the term “risk” in project management what we are really measuring is the entropy in the system. No system returns 100% effort from its inputs; there will always be loss.

We develop our plans to incorporate risk acknowledging this reality. Thus, our project plans—assuming our framing assumptions are correct—become a balance between managing risk and managing performance against the plan.

Information and Learning is the Key

We must borrow from other systems in order to keep risk from manifesting in a way that it undermines the project framing assumptions and project resource constraints, and consequently, degrades the technical achievement resulting from the effort. To overcome implicit risk, baked into the effort, we must find a multiplier so that we can “run twice as fast.”

Experience has shown that measures of technical expertise and performance are the only variables that have ever provided this kind of effect when it has been needed. Today, this is known as the growing field of Model-based Systems Engineering (MBSE) and the multiplier provided through digital engineering.

Only then can our time-phased plans, which must be tied to the achievement of work, accurately reflect and influence the chain of events (time) that must be achieved and leveraged to successfully conclude the effort. After all, these are engineering and science projects, not earned value or project performance projects, the latter categories being important, but not overarching or of primary importance.

You must be logged in to post a comment.